Boxes

The boxes from this phase form a very homogeneous group, an iconographic programme, a story made up of chapters in which the theme changes but the syntactic structure is repeated. There are two types.

On the one hand, the medium and large sized boxes. Most of them are small trunks which were designed at the time to store the samples that an oil company offered its customers. Some of them were left over and remained dull and dusty in the company’s warehouse. A brother of Trinidad Irisarri, one of Pilar Lara’s studio colleagues, offered her the boxes, as he knew full well that she was looking for this type of containers. She had already produced works such as ‘Leñera’ and ‘D(esposada)’ using wine boxes, without a lid, inspired in niches or domestic shelves, as in ‘Ingredientes para el chorizo’ [Ingredients for chorizo], rather than small chests and furniture giving shelter to memories, old photos, letters from an old love, little intimate treasures…

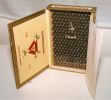

On the other hand, cigar boxes, almost thirty works. Here Pilar is certainly inspired by that typical and secondary use of boxes: who has not ever stored sometime marbles, collectable cards, stamps, photographs, letters, keys and so many other small objects with a unique and personal value that nobody, except the owners of such treasure, understands? Frequently, the owners were children and teenagers who tried to create their first private and individual space, facing the curiosity of adults. Pilar also recalled this way, and she will do it from now on until her later works, that lost innocence of childhood, that clean look, unstained, fearless, full of hope, through which she wanted to continue watching the world. Even to reveal the things she did not like of that world without false pretensions, as only a child can do.

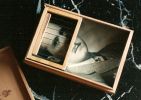

Both the small trunks and the cigar boxes preserve their lids. The art work is kept inside, and the boxes have to be opened to discover it, with a mixture of curiosity and guilty conscience, uncertainty and unhealthy interest in somebody else’s privacy, without knowing the secrets that can be revealed or if there is any right to access them. These boxes contain a ‘surprise’. Pilar did not take part on the outside of the box. Nothing indicates what can be found with the box locked. There are no clues. A box is similar to the others, they are subject to an industrial uniformity. For the same reason, they are difficult works to exhibit and collect- actually, although people liked them, Pilar could only sell a handful of them-. They are for the personal enjoyment, intimate –as the world they conjure- of those who have them…These works should be treasured and opened once in a while, alone, to be surprised every time you get carried away by the curiosity of ‘sniffing’ around.

As conceptual works, many are based on an action, sometimes previous- the systematic collection of metro tickets during the trips to the heart of the city preceding ‘Pitillera’ [Cigarette case] -and sometimes carried out during the production of the content of the box- the insertion of nails and keys while forging the wax in ‘En boca cerrada’ [Closed Mouth] or ‘Emilia’, the pellet shots on the plate in ‘Atentado’ [Attack], and the cracked eggs when lowering the cover in ‘Masculino- Femenino’ [Masculine-Feminine]-. Other works are not complete if some candles are not lit- as in the previously mentioned ‘Leñera’- or are an invitation to interaction- as it happens with the spinning top in ‘Ambigüedad’ [Ambiguity], the tin opener in ‘Cárcel’ [Prison] and the already mentioned ‘Ingredientes para el chorizo’-, anticipating the series of games she will produce next. Sometimes they also include a mechanism that works if it is activated- as in ‘El Riesgo’ [The Risk]. All these works are alive, they were thought as an extension of life and have an intention to be reintegrated into the everyday life, bringing back their deliberate message in the original contexts.

Pilar Lara produced the largest set of boxes on the occasion of the solo exhibition that took place in Alcalá de Henares as part of the 1990 Ciudad de Alcalá award, at the Capilla del Oidor, from March 11th to April 11th in 1993. She worked systematically for two years in order to produce thirty of these pieces, and she was worried about the room size and the difficulty of ‘filling’ such a big space with a very small collection of works. But she was successful. The works were exhibited in small groups- some on old pieces of furniture that Pilar transformed into exhibition supports, as a suitable set design counterpoint -, arranged wisely and, thanks to a good lighting, they made such a strong impression that people only had eyes for them, so that outlines and room size were blurred. The tour of the exhibition was full of surprises, fostering curiosity. From one corner to the other not knowing what could be found, hidden behind the external silence of the boxes, without the prospect of the large-format works on the walls or on a pedestal. The feeling was like that of someone going through the hidden corners of a house, of a life, opening the drawers and discovering the fragments of a mosaic in which the drawing starts to be discerned only at the end. Pilar was very proud of this exhibition. It represented, together with the award, a support for the new approach to her work. But, most importantly, she never had the chance to achieve such an appropriate symbiosis between her works and the exhibition space, either before or after, and create such a coherent story between her art pieces and the setting where they were arranged. During those two years she was preparing the exhibition, as she was familiar with the place in which the works were going to be exhibited, she always had in mind that space and its connotations, a continuous and inspiring reference. For that reason, the exhibition became a reality in her mind first, as the conceptual artist she was, and would after take shape in such a ‘natural’ way at the Capilla.

In the words of Gabriel Villalba, the Fundación Colegio del Rey’s director: ‘The main characteristic of Pilar Lara’s plastic concept is the strict thoughtful maturity, and that has been this artist’s course of work recently, considered, expanded and refined to the point of extreme rigour’. ‘Pilar Lara works with her thinking and with each of her works, she opens us up to all the poetry, all the analytic sense she has enclosed before in her boxes-works using a refined thoughtful process’. As for Javier Maderuelo, in the catalogue of the exhibition, he states: ‘Each object has a given place in the house […] so that each showcase, each sideboard, become an altar, the placement of the emotional resources […] embraces the value of cult elements […] since […] through those presences, those recalled moments and people are revisited and relived […] Pilar Lara makes use of these objects without expecting a ‘conceptualisation’ of its uses and contents, but rather establishes with them some disturbing combinations that surprise us […] Whereas pop-art celebrates the images of everyday mythology, Pilar Lara’s works claim the suffering condition of the antihero. […] She recovers the obvious and the intimate and decontextualizes it, not to amplify it, but to reduce it to a personal and unique experience. With those universal elements, omnipresent in all households, she reconstructs a personal story: her own story’. It should be added that it is a personal story that has the ability to become a collective one through the use of codes shared by a whole society. It expresses the concerns and experiences of, at least, two or three generations of Spanish, especially women.

Let us see, in that sense, which issues are ‘enclosed’ in those boxes. First of all, several reflect on the female condition - in line with one of the main concepts in the artist’s work-, on how our culture has pushed her into a background role: wasting her life at the service of family- as in ‘Leñera’-, trapped in her role as a wife and mother- as the chains and bottles of milk in ‘D(esposada)’ suggest, or as ‘Contenido’ [Content] proposes, the box becomes an allegory of the womb and is one of the few where the outward appearance is significantly not silent-, limited to certain types of alienating jobs – as in ‘Costurero’ [Sewing Box]-, shut into her domestic labyrinth awaiting the husband’s arrival- as it happened to ‘Penelope’- or mutilated by the same man- as it happened to ‘Santa Rita de Casia’ [Saint Rita of Cascia]-. In ‘Nuestros hijos’ [Our sons], there is also a homage to all those mothers who were ‘mutilated’ by the loss in the war- in any senseless war- of the sons they had raised, mothers who dedicated their lives to them. Those sons who had become cannon fodder, pawns on a chess board, insignificant lives like the ones of the insects poked in the entomologist’s tapestry- as in ‘Voluntarios’ [Volunteers]-. ‘Sálvese quien pueda’ [Every man for himself] protests against the indiscriminate violence of war, and ‘Soldadito español’ [Spanish soldier] and ‘Pesadilla 1938’ [Nightmare 1938] against the injustice of a very concrete war. In the latter one, she uses remains of the shells collected by her children in the fields near the family’s summer holiday location: Villanueva de la Cañada, that is, the old battlefields in the Brunete’s front. ‘Sin título’ [Untitled] stands up against domestic violence, and ‘Atentado’ and ‘Cárcel’ against any type of violence. Another series of works reflect on the relationships between genders: ‘Historia de amor’ [Love story], ‘Masculino-femenino’, ‘Están’ and ‘Complementarios’ [Complementary]. Others reflect on the age of innocence, when there is a whole life to be built: ‘Inicios’ [Beginnings], ‘Vacío’ [Emptiness] and ’16 de enero’ [January 16th]. Others, on the physical fragility of the human being: ‘Fumar perjudica seriamente la salud’ [Smoking seriously damages your health], ‘Pitillera’, and of course, ‘Corazón’ [Heart]. Others, on the fragility of nature: ‘Árbol urbano’ [Urban tree] and ‘Energía’ [Energy].

Finally, another set of boxes is related to the mysteries of the human mind and the human behaviour: ‘¿?’, ‘Cerebro visual’ [Visual brain], ‘Pirómano’ [Pyromaniac], ‘Ambigüedad’, ‘Fragmentos’ [Fragments], ‘Alzheimer’, ‘Esquizofrenia’ [Schizophrenia] and ‘Mente’ [Mind]. This group, monographic and especially meticulous, comes after the exhibition in Alcalá and represents a return to the concern about the dark, irrational and uncontrollable side of the human being.