Nightmares and The Apocalypse (1984-1987): Oils and Acrylics

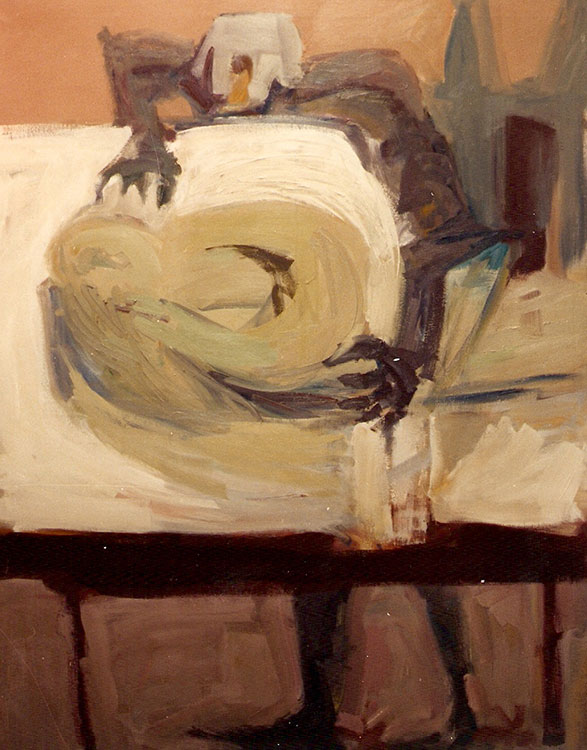

During these four years, Pilar Lara produces more than sixty works, forty eight of them are presented here. They are mostly oil paints and acrylics on canvas, although sometimes she changes that support for a panel, a paper or, as in the first works between 1984 and 1985, printed fabrics, sometimes as the only base, sometimes glued to the canvas. She also paints many sketches and testings on paper.

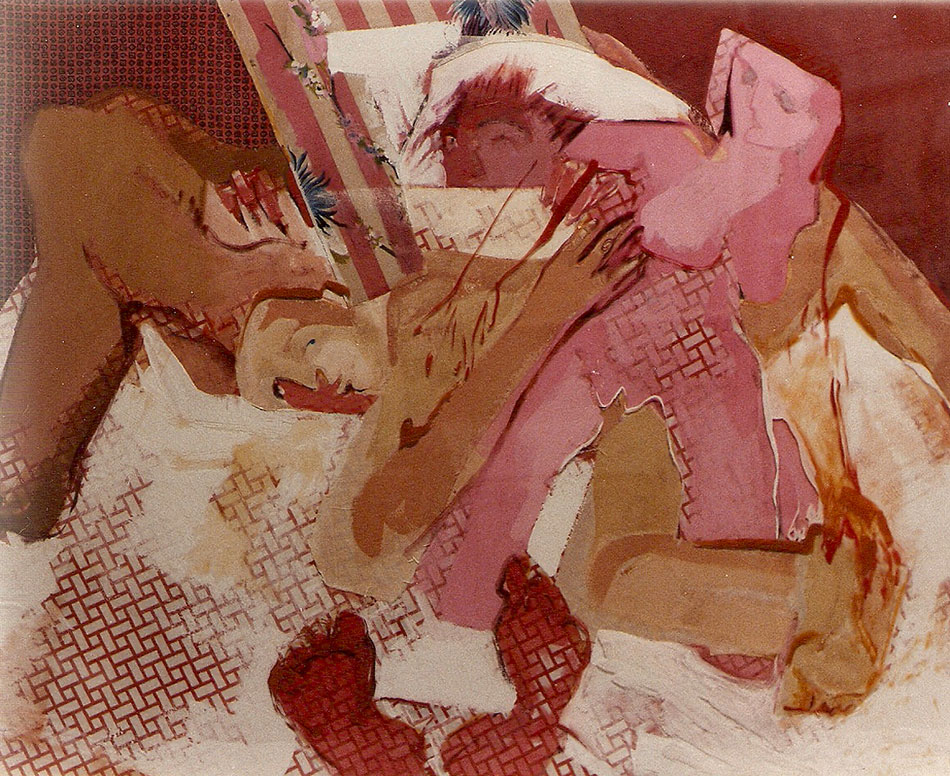

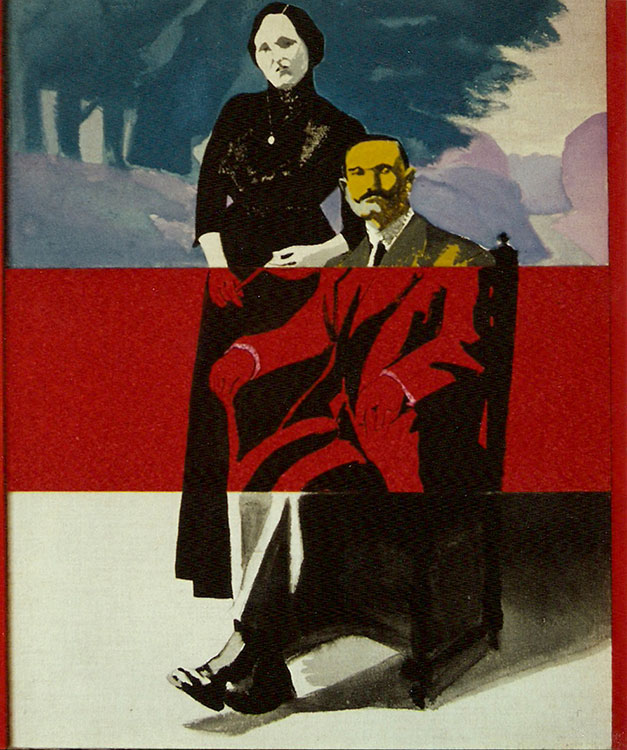

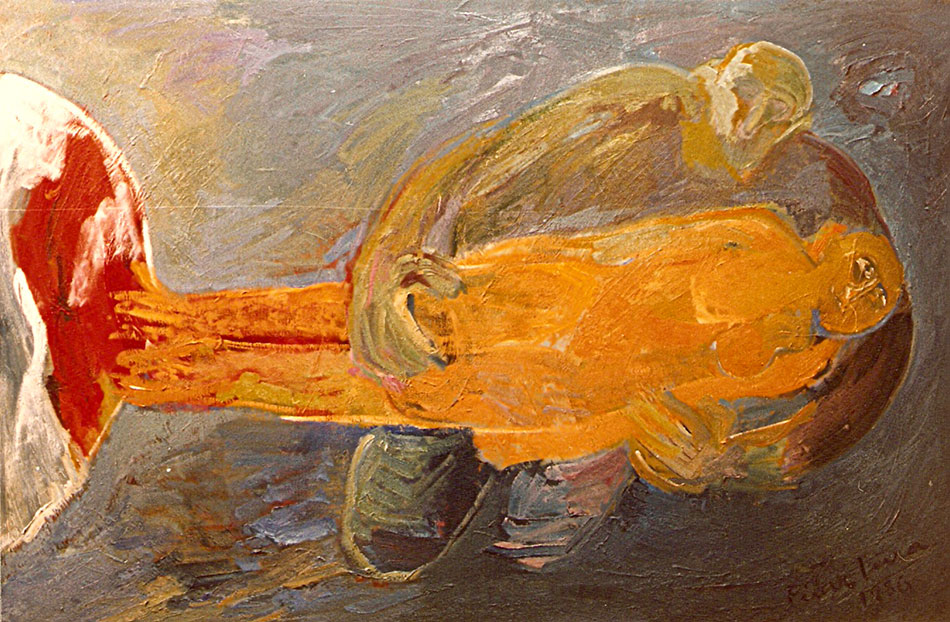

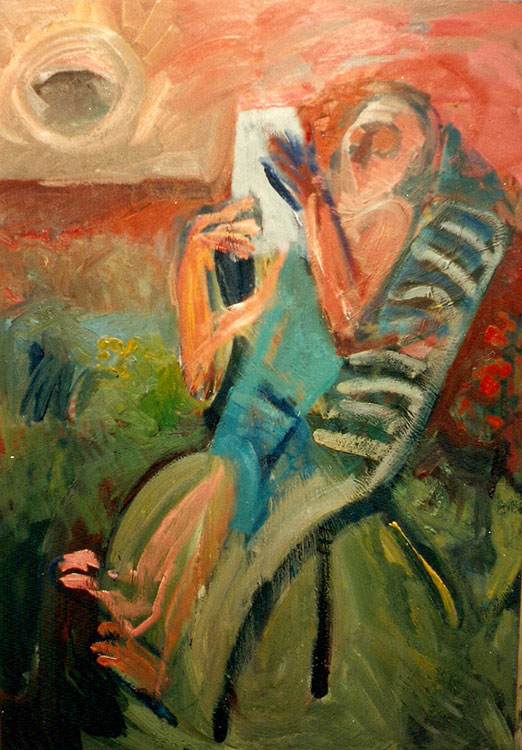

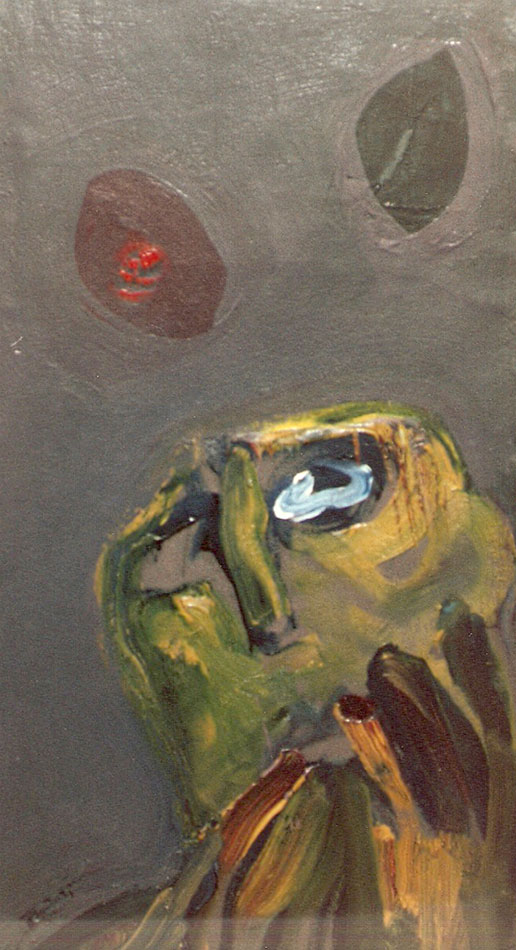

In those first works, the love scenes typical of the watercolours and engravings still appear. But they are soon replaced by others where it is perceived a feminine figure who gives in, motionless, to the arms of mythical creatures, half man, half beast- as in the significant ‘Fantasma de la Noche’ [Ghost of the Night]- or even monstrous beings. She is also carried by winged creatures in a ‘Vuelo cósmico’ [Cosmic flight]. The reason of this mutation can be found in ‘Lovecraft’, a work in which a woman is surrounded by billy-goats. It pays tribute to the master of horror fiction books and his work, characterised by violent and elementary drives, the nightmares that show the other side of our ordered world, the legends about the dark side of the human being, our animal condition, the chaos of the subconscious, and especially, the sin that embodies all the monstrous and demonic. The sin, the original sin, inherent to the human being, and his dual nature of man and beast, angel and demon, can also be found in the two works dedicated to Adam and Eve.

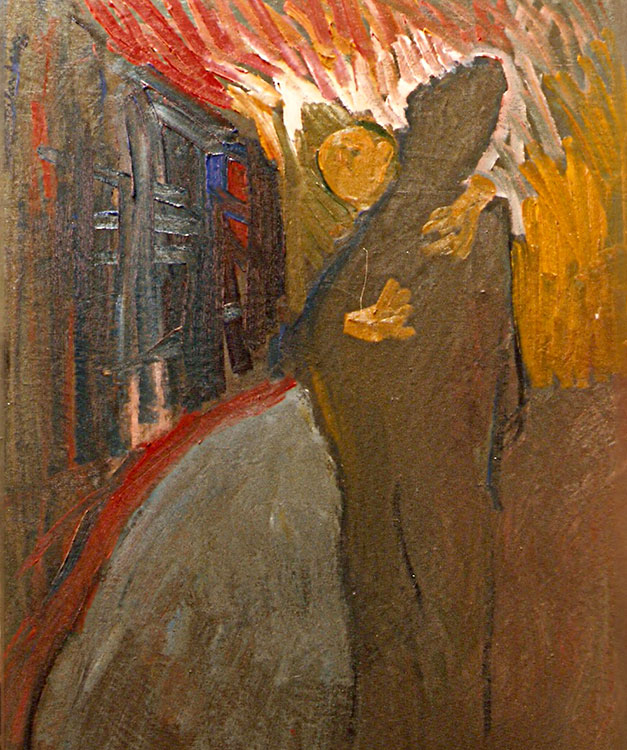

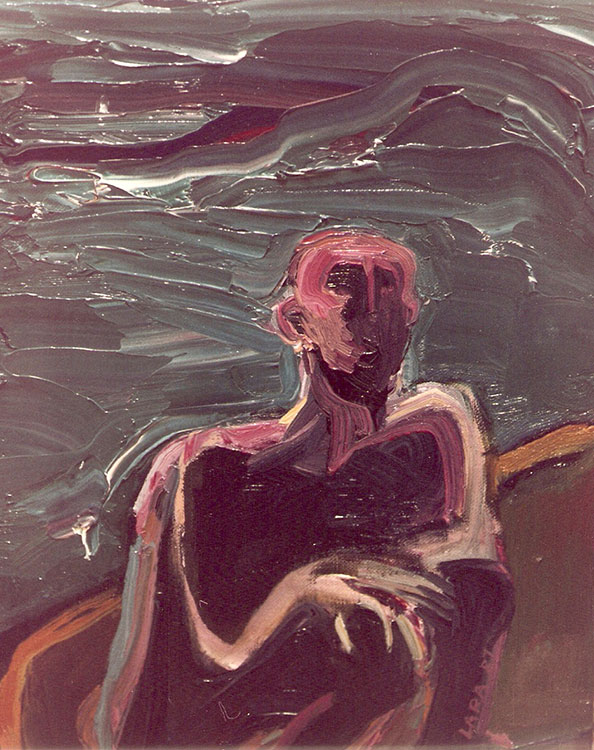

At the end of 1985, the themes Pilar Lara called ‘cosmic’ will appear. Not anymore the nightmarish flights recently seen, but allegorical compositions featuring vague figures facing the immensity of the universe and its unleashed forces- which escape the insignificance of man, so there is little he can do- or the forces called by the human being himself, moved by his greed, arrogance and recklessness- there is little he can do either, since he is a victim of his own sentence. This series begins significantly with ‘Apocalipsis’ [Apocalypse], a mushroom cloud, and finishes turning to biblical themes with ‘Jinetes del Apocalipsis’ [The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse], a composition where the tendency to a certain expressionist abstraction reached its peak. Here, the horses and the beasts take up all the space, and the insignificant horsemen disappear. In some of these works, the apocalyptic moment could also be interpreted as a ‘genesis’, where destruction is necessary as a way of regenerating, a catharsis, and at the same time, presents the idea that the Universe, after all, was formed through an explosion, a Big Bang- a theme she will use again in the last phase of this stage.

During the year 1986, these themes coexist with others that tend to extend the reflection on nightmares and the other side of the subconscious: witches in ecstasy, helpless beings going hunting under the moonlight and allegorical beasts. The Freudian interpretation of dreams also appears in the re-reading of some classic tales. They certainly hide a terrible dissection of the human soul behind its sugar-coated children’s version. For example, in the Sleeping Beauty or Snow White. The human distress, his loneliness in the immensity of the universe and his existential anxiety can be found in works where figures appear under the sun, in the middle of a large water zone or killing themselves.

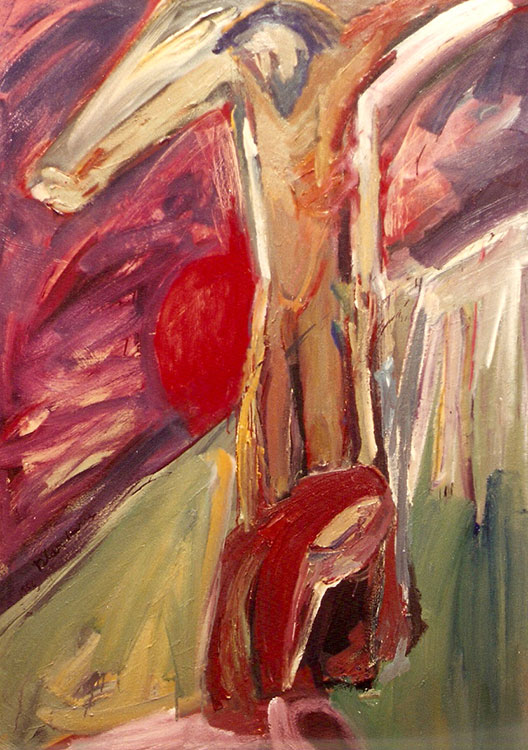

Could that human being condemned in advance be saved? Does redemption exist? Is there any future for a world doomed to self- destruction? Is the series of crucified, again a religious theme, an effort to reflect on this matter taking into account the Christian education of the artist? They are certainly not serene figures, liberated through sacrifice. They seem to cast some doubts on the canonical interpretation of the death of Christ: watching them, it prevails the feeling of an absurd and violent death, without any divine aura, the destruction of a life at the hands of men, the unjustified martyrdom of a human being. Is there any veiled criticism of the fact that the Church had made use of this death to spread its message of faith? Of the fact that the most significant moment of its doctrine sublimates a violent act as well as builds a moral around the idea of sin and purification through suffering? It could be possible, although it may seem contrary to the message sent by some of the other works. However, it seems like the contradiction and the dialectic struggle are typical of this creative period: Pilar Lara was definitely reviewing her own beliefs through her creations, reflecting them in the most paradoxical way. In these works, there is a certain metaphysical and existentialist consideration, halfway between The Gay Science by Nietzsche, screened by a Lovecraftian style, and the Gaia theory: the human being in conflict with creation and his own raison d’être, and at the same time, in his arrogance, facing the possibility that the forces of the universe annihilate his uncomfortable existence.

With these models, the works of this period inevitably have a symbolist nature, following the path stated in the previous phase (‘Sueños’), but only on a conceptual level, since the language changes completely. It is entirely expressionist now, visceral, based on violent brushstrokes and radical colours, unnatural, or rather, supernatural. The night scenes, the backlight, the outlined silhouettes on a source of light that might be the moon, a fire, an explosion, a reflection…Apart from the cosmic compositions, there are plenty of outdoors scenes, located in ghostly landscapes. Although it is barely perceived, the context is reduced to just a few references. The system of proportions meets an internal order, surrealist. As in a nightmare or hallucination, the images appear distorted by the imagination, and the distortion adds tension and paroxysm. There is no doubt that this catalogue of images defines a world of its own, very personal, consistent and recognizable. Viewed as a whole, it can be appreciated that, despite the spontaneity of its execution, they are actually the accomplishment of a painstaking programme that becomes a true iconographic system.

During these years, Pilar continues sending her works to many contests and competitions throughout the country. She was highly commended twice at the Certamen Nacional de Pintura de Luarca [National Painting Contest of Luarca] in 1985 and 1987. Asturias is one of the places where her work is greatly valued, because a few years later she will find certain success at the Biennial Painting contests of Sama de Langreo. As a consequence, the artist’s production is better represented in the Asturian public collections. Anyway, the ‘debut’ of the works of this phase took place in the second solo exhibition of Pilar Lara (the third if we add the one in Úbeda). In April 1987, at the Gregorio Sánchez foundation, Pilar made public twenty-two of these paintings, the most mature, chaired by the quartet of ‘Jinetes del Apocalipsis’, a series that she considered the highlight and swan song of this period of her career.

Indeed, a few months later, Pilar successfully underwent a delicate heart surgery. Not only would this lead to a several months break, before and especially after the operation, but it would change her way of understanding art, as she was inevitably doomed to a period of reflection, and certainly had to face also a physical and emotional test. She got back to work with renewed strength, but her expressive needs were now different, not so energetic and visceral, but more slow-paced and reflexive.